Life on the Cliff's Edge: On depression and anxiety

Today is the last day of May, which is also mental health awareness month, and this year I've decided I'm ready to share my story. Most people who know me know that I suffer from depression and anxiety, but until now, I haven't widely shared the details or the extent of my experiences. To most, I probably seem high-functioning, if a little eccentric. The stories we tell about mental illness usually revolve around characters who are either in the middle of a crisis or who have "gotten better" through treatment. But my story is different, and I suspect that to be true for many people living with mental illness. My story is one of a constant struggle to avoid crisis. It's like living life walking along the edge of a cliff. From a distance, everything looks fine, but a single misstep could be catastrophic.

I've had the mixed blessing of learning this second-hand, by observing my family. My older half brother, Bily, struggled with Bipolar Disorder and heroin addiction until he ended his own life in 2009. My younger brother, Doug, has spent the majority of his adult life indoors, incapacitated by a cocktail of antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers. And my father's anxiety, depression, and alcoholism led to him spending half a decade homeless, sleeping on a piece of cardboard outside a bus station. People who know my family always comment with awe at how differently my life turned out. The irony is that there's only one real difference: I saw the cliff before I fell off. Mental health is the first consideration in every decision I make, which tends to baffle a lot of people. So often I'm asked "Why can't you just do what everyone else does?" But "everyone" doesn't include everyone incapable of leaving their house, or everyone living on the street, or everyone who has ended their own life.

So how do I stay healthy? I don't use alcohol, nicotine, opiates, or prescription stimulants. When my panic attacks became debilitating in 2007, I gave up caffeine. I'd been drinking 15-20 cups of coffee per day because I was too tired to do anything without it. The panic attacks subsided into a slow burn of generalized anxiety, but I needed a way to improve my poor sleep. After years of experimenting, I found that a combination of morning light therapy, wearing blue-blocking glasses in the evening, and a regular schedule of 9 hours of sleep at the same time every night allowed me to function. People are often envious that I get 9 hours of sleep every night, but are less envious when I leave parties to go to bed at 10pm on Friday night so I can get up at 7:30 on Saturday. I resisted antidepressants for a long time because I was afraid of altering my thinking or further muting my already dull emotions. But then, things got worse.

In 2011, my stress level hit an all-time high. My father was newly homeless after a divorce. My own relationship of 3.5 years had ended in pain and humiliation, cutting me off from what had become my adopted family. And my childhood cat, Cotton, died. At the time, I was freelancing and working from my one-bedroom apartment, which is a perfect combination of anxiety and isolation. Soon I wasn't well enough to take on new work, and I was burning through my savings to support myself. Things peaked after fall daylight savings threw my sleep schedule off. For about three weeks, I was in constant and excruciating mental agony as bad as any physical pain I've ever experienced. My one goal was to find a way to lessen the pain. I spent every day trying to find people to talk to, just to get outside of my head, and the high point of my day was slipping into unconsciousness at the end of it. I was willing to try anything, and I finally made an appointment with a therapist and a psychiatrist. It was a couple painful weeks before I was able to meet with them. In the meantime, I made a chart of my friends. When I needed to talk to someone, I called someone I hadn't talked to in a while. I made a note of the date each time so I wouldn't lean too hard on any one person. I made it to my appointments. Therapy helped. Antidepressants helped. Things slowly got better.

Over the course of 2012, I learned to be happier than I'd ever been before. Antidepressants, combined with regular exercise and sleep, made it possible to fully experience happiness, but it was up to me to find things that brought me happiness. I learned to temper my ambition and focused on connecting with friends. I spent more time with groups of friends, which helped create a positive environment even when my mind was stuck on negative thoughts. I began inviting friends over and making crepes for them, with everyone bringing their favorite toppings. The tradition has only grown in popularity since then. By the end of the year, I finally had a pretty good idea of how to manage my mental health.

So now I know what I need to do to stay healthy, but it's still a constant struggle. I minimize my commute time so I can have social time left over after work and still get enough sleep. I try to find ways to spend time with friends who are used to party o'clock starting at 10pm. I am eternally in search of a convenient place to put my wet gym towel in the morning. I start shifting my sleep schedule weeks before daylight savings. I schedule and plan and focus my work time to increase my efficiency. And if I get off of my sleep/exercise routine, I fix that before anything else. I've been glad to see compassion for and awareness of mental illness becoming more common. And I'm looking forward to a time when the focus shifts from fixing people when they break, to accepting and encouraging ways of life that don't break people in the first place. I'm looking forward to a time when those of us who live on the cliff's edge are respected for the weird dance we do to avoid it.

Liveblog: Creating Radical, Accessible Spaces

These notes were taken live at the University of Michigan School of Information on October 23, 2015.

Panelists:

Jane Berliss-Vincent: Assistive Technology Manager at the University of Michigan, author of Making the Library Accessible for All.

Terry Soave: Manager of Outreach & Neighborhood Services at the Washtenaw Library for the Blind and Physically Disabled and Ann Arbor District Library.

Carolyn Grawi: Executive Director of the Center for Independent Living.

Paul Barrow: Public Services Librarian at MLibrary.

Joyce Simowski: Information Services/Outreach Librarian at Canton Public Library.

Melanie Yergeau (Moderator): Assistant Professor at University of Michigan Department of English Language and Literature, with a focus on Disability Studies.

Melanie begins by introducing the panelists. Paul works on facilities and front desk issues. His first job was working for a man with Cerebral Palsy and the lessons he learned have stayed with him. Joyce works with older adults. Jane, a UMSI alum, wears many hats, including makeing sure the University of Michigan public computers have accessible technology, and collaborating on web accessibility. Terry builds partnerships with community organizations in order to reach populations that aren't typically engaging with library services. Carolyn works with individuals having many types of disabilities at the Center for Independent Living, and has more than one disability herself.

Paul has increasingly observed that individuals with disabilities are not identifying publicly and asks how to help them. Carolyn suggests making it clear on materials that it's ok to ask for accommodations. Some accommodations can be expensive, but if you know ahead of time which ones are needed, you can avoid unnecessary expenses. Terry stresses that you have to know your community because it's impossible to accommodate everyone all of the time. You can put up a sign, but if someone can't read it, what do you do next? Terry adds that it's very challenging to understand the things that you take for granted when working with someone who has a disability. Terry tries to make it easier to do that.

Jane tells a story about going to AADL with Jack Bernard, Associate General Counsel at UMich. They went around to different desks and asked whether the library had accommodations for disabilities. Everyone was respectful and knew how to access resources. Carolyn adds that when those resources are easily available to the disabled community, they are beneficial to everyone.

Jane describes how universities are accommodating a wider range of disabilities: learning disabilities, etc., when a couple decades ago, the university worked mostly with sight disabilities.

Audience question: Is anyone providing healthcare accessibility?

Jane: receiving healthcare often involves filling out inaccessible forms with small print, which may not be available in languages other than English. Carolyn just met with a group of medical students learning about compassionate care. There's definitely involvement, but she wishes there was more. A lot of what already exists would benefit from being more standardized. Medical students have to meet with community services, but not every student can meet with every service. It's key for those students to share their that information with each other. She adds that it's important to include the person with the disability: "Nothing about us without us."

Melanie asks whether anyone is collaborating with disability organizations. She gives the example of autism. In autism awareness month, groups like libraries can create well-meaning but ill-advised displays and programs, like advertising organizations that promote misinformation, offering programs that exclude the autistic individuals. Jane talks about the importance of a back and forth dialog. You can't know what people want unless you et them involved and ask them. Carolyn: the Ann Arbor CIL works closely with many organizations. One example was working with the AADL to make the front entrance more accessible. Collaboration isn't always simple, but it's beneficial. Carolyn gives another example, of working with fourth graders in public schools. Why fourth graders? They are at an age where they are open to learning, like to share what they learn with each other, and speak up about the things that they need themselves. A student who had taken one of the workshops once ran into the workshop leader at a theme park and told them what they thought the park was doing right and wrong.

Audience question: How to you ensure that the population you're serving is aware of your services? Terry has outreach staff, works with doctors offices to put information in waiting rooms, and also provides institutional accounts to other institutions that may be working with elligible individuals. By far most people learn about services by word of mouth. Places a sticker for a large-print service inside all of the library's large print books. People like to help, and making connections is an easy way to help. Carolyn: now you can access a lot of materials digitally, so you don't need to come in physically. That can be good for individuals with disabilities but can make it difficult to provide them with information.

Joyce tries to determine and respond to the needs of the community. Carolyn: we all try to follow the ADA and provide "reasonable accomodations." Jane brings up small, light-up magnifiers. They're useful and inexpensive and can be used to provide information to people who need them.

Audience question: how do you deal with the challenge of helping disabled individuals be courteous to those with other disabilities. Jane: sometimes you have "dueling disabilities" like someone who turns a monitor off because the light is a problem, but someone else might not be able to figure out how to turn it back on. It's a challenge. Paul thinks libraries are special because they are a center for conversation. Paul gives the example of moving power outlets from the wall to the table to prevent creating tripping hazards with power cords. Just having a conversation is very powerful. Humans are reactive by nature, so let's react by having a productive conversation. Carolyn agrees that libraries are one of the best places for different types of people to get together.

Audience question: Has background in rural libraries. If you have limited resources, what are the core principles you encourage a library or other public organization to pursue. Jane: listen to your patrons. Finding out what people need may be easier in a small group. Carolyn: maximize your open space. It's useful to more people. Joyce: partnerships can help, like having meals on wheels deliver books. It can be hard to do these collaborations unless they're mutually beneficial, so the collaborations have to be found on a case-by-case basis. Terry: different organizations have different types of funding, which affects which types of collaborations are easier. Paul: libraries used to brag about collections, but they're all the same now. Instead, focus on services. Jane: libraries are not just book collections anymore. In rural areas, they may be points of access for the Internet or job searching.

Audience question: The term "universal design" gets thrown around a lot. What are small changes that make things better for everyone? What is a radical accessible space, and where have you seen one? Jane: Interested by the convergence between "bring your own device" and accessibility. Now universities are moving towards "bring your own everything." Many of the features being used on mobile devices are taken from assistive technology: autocomplete, zoom. The first typewriter-like device was developed by Pellegrino Turri to write letters to his blind friend, Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano. Carolyn: we try to describe attachments. Having inclusive seating helps: making different types of seating (front, back, etc.) accessible. It's important to be open to feedback and take it as constructive even if it seems critical. Paul wishes that physical spaces were more configurable.

Audience question: The state is putting accessibility as a low priority. What can we do to make it a higher priority? The CIL has ongoing discussions with the state legislature, but sometimes difficult to make progress because of a lack of bipartisan interest.

Closing comments. Jane: think holistically. A towel dispenser may be ADA-compliant, but it doesn't help if you place it where someone in a wheelchair can't reach it. Joyce sees advancements in technology as making a big difference. Be observant of what people need. Carolyn: be patient and tolerant if someone asks for something you don't know or isn't understanding something. Paul: be radical, do what's right, not what people did before.

New Hackerspace Design Patterns

The wave of hackerspaces in the US over the last decade was triggered, in part, by the collection of the hackerspace design patterns, best practices that had been developed in European hackerspaces. This year at Chaos Communications Camp, Mitch Altman will be presenting an updated list of hackerspace design patterns and has asked the community for input. Here are my contributions based on several years of hackerspace administration.

Sustainability

Replacement Pattern

Problem: Volunteer roles require developing new skills and learning from the successes and failures of past volunteers.

Solution: Volunteers should start training their replacements as soon as they take on a role. Having more members with the necessary skills will make it easier to find a replacement when the time comes. Also, the more members who understand a particular volunteer role, the easier it will be for the volunteer in that role to communicate with the membership.

Principles Pattern

Problem: Members in a large group have different values, making it difficult to make decisions.

Solution: Early on, create a list of "common principles" or "points of unity" that describe the ideals that were important to the early members. These ideals should be explained to all new members. Debates should be framed in these common principles. Principles can be revised, added, or deleted, but only if there is consensus.

Mentor Pattern

Problem: On-boarding new members is difficult. New members can have trouble finding the resources they need and learning their responsibilities as members.

Solution: Every new member is assigned an experienced member as a mentor. When the member has a question, they can go to the mentor to find the answer. If the member is acting out of line with the group's principles, the mentor can talk to them.

Caretaker Pattern

Problem: There are a lot of space usage decisions to make, but most are irrelevant to any particular person.

Solution: Appoint a caretaker for each zone in the space (machine shop, craft room, etc.) The caretaker's contact info is posted publicly in that zone. If a member has a question or a problem in that zone, they can contact the caretaker to fix it. The caretaker gets final say on space usage decisions.

Outreach Pattern

Problem: Your space is almost entirely young, middle-class, white men and anyone else feels less comfortable using the space.

Solution: Actively increase your group's visibility in communities with higher percentages of women and underrepresented minorities. Place more flyers, advertise on mailing lists, and give these groups advance notice of classes and workshops before announcing them to current members and their friends.

Pot-Lock Pattern

Problem: Maintenance and cleaning is boring and no one wants to do it.

Solution: Hold a combination pot luck and lock-in. Everyone works on maintenance and cleaning and takes a break to share home-cooked meals with each other. No one leaves until time is up.

Conflict Resolution

Signage Pattern

Problem: Members aren't doing something they should.

Solution: Put a signs explaining correct procedure as close to the problem as possible, e.g. stencil "Clear off before you leave" on flat surfaces.

Physics Pattern

Problem: The group makes a lot of rules, but they are often ignored.

Solution: Instead of creating rules, make it physically impossible to do the wrong thing, e.g. instead of saying "turn the lights out when you're done," put the lights on an automatic timer.

API Pattern

Problem: Hackers don't like unnecessary rules, and rules are often unenforceable.

Solution: Instead of rules, create procedures for solving problems. For example, create a "parking ticket" that members can place on abandoned projects in their way, and a standard way to notify the group about the ticket. Allow anyone to dispose of an abandoned project a certain amount of time after a parking ticket has been issued.

Anti-Popularity Pattern

Problem: Conduct complaints turn into popularity contests.

Solution: When discussing conduct complaints, judge actions instead of character. Be clear about which specific actions were inappropriate and why. This has the benefit of reinforcing behavioral norms for other members.

Dossier Pattern

Problem: The board has received a complaint about a member, but the member says they didn't understand the rules. The board members are new and have no way to know whether the member has been a problem before.

Solution: Keep records of all member complaints in a system that is confidential and searchable. Even if someone doesn't want to make a formal complaint, leaving a note can help establish whether there is a pattern of misbehavior and help future boards follow up.

Anti-Kibitzer Pattern

Problem: Everyone has an opinion on how a task should be done, but no one shows up to do it.

Solution: Make it so that members have to put some effort in before they get to have input. Have discussions in committee meetings outside of general meetings, and require homework (e.g. email in proposals beforehand). If someone doesn't show up regularly, or doesn't do constructive work, stop inviting them to the meetings.

A graceful end to Seltzer development

The Kickstarter I’ve been running for Seltzer (a tool for managing cooperatives) finished last night, at just shy of 1/3 of the funding goal. While the project wasn’t successfully funded, the crowdfunding campaign was far from a failure.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve learned an incredible amount about who is actually interested in Seltzer, and how much they’re able to participate. I received dozens of encouraging messages from organizers and administrators telling me how much they needed software like Seltzer. And I'm incredibly grateful to everyone who did pledge money to the project. I know many people stretched themselves to give generously. But, in the end, it wasn't enough to fund the project. Several people have told me I should have done an Indiegogo so I’d still get the money that was pledged, but here’s the secret: the campaign was as much about gauging interest as it was about raising money. The main goal of Seltzer has never been to create an application with a specific set of features, but to cultivate an open source community that could work together on an application that meets their common needs. No amount of money can buy that. Now I know that the time isn’t right, and I can apply myself more effectively elsewhere.

So what specifically did I learn? I had expected most of the support to come from people and organizations that were already using Seltzer or at least knew what it was, but I found just the opposite, which might mean that the existing version is actually good enough for everyone using it. I’d also expected many more small-dollar donations but was surprised to see that I got more $40 donations than $10 or $20. Data management isn’t sexy, so I realize now that those small dollar donations needed a more exciting reward to overcome the "sign into Kickstarter" activation energy.

I’d also expected more support from existing hackerspaces, both in the form of larger pledges and encouraging members to make smaller pledges. Members of a few spaces did take this on, but not as many as I’d planned on. The biggest challenge was establishing and maintaining contact. If I could do it again, I’d have started reaching out to hackerspaces months earlier and held regular calls to keep the momentum going. Volunteer organizations move slowly, and are easily distracted.

I’m a little sad that the campaign didn’t get funded, but it’s important to know when to end a project gracefully. So what does this mean for the future of Seltzer? Well, I won’t be developing a new version any time soon. Instead I’ll continue answering questions and reviewing bug-fixes, but no new features, on the existing version. Edit: And don't forget, you can still write your own modules to integrate with the existing code! I’ll also continue organizing people around cooperative software and linked data. If you want to be involved, join the cooperative software mailing list. I’ll also keep following exciting tech developments like JSON-LD. Who knows, maybe there will be a resurgence in interest for Seltzer later on, and I'd certainly consider another crowdfunding campaign, maybe over summer in some future year. In the meantime, it looks like I'll have four-day weekends for the rest of the this summer, so I should be able to relax a bit and catch up on reading and other side-projects.

Art, Code, and Asking

As a programmer, I know that code can be beautiful. As an artist, I know that code is not art. I don’t mean to say that code is in any way less, just different. And the difference is important, particularly when it comes to asking for support.

It’s a very exciting time for artists, as many turn to crowdfunding to support themselves. Either through single-shot funding campaigns, or ongoing patronage, artists are asking their fans for direct financial support, and fans are happy to give. The Boston-based musician Amanda Palmer has led the way, raising over a million dollars on Kickstarter to produce her most recent album. She reflects on the campaign in her book, The Art of Asking. In a passage that hit particularly close to home for me, she recounts a conversation with her mother, a programmer. As a teenager, Amanda had accused her mother of not being a “real artist” and years later, her mother told her:

You know, Amanda, it always bothered me. You can’t see my art, but… I’m one of the best artists I know. It’s just… nobody could ever see the beautiful things I made. Because you couldn’t hang them in a gallery.

Amanda came to recognize the unappreciated beauty of her mother’s work, and I have no doubt it was beautiful. But art is not just about beauty.

A few years ago, I was sitting in a client’s office in San Francisco, at a tiny desk overlooking the Highway 101 onramp, listening to music and writing code. The music was beautiful, but more than that, it showed me an entirely new perspective, that somehow felt deeply familiar. And in that moment, I felt a little more connected to humanity, and a little less alone. But I was sad to realize that my work would never help anyone else feel that way. I remembered a quote from Maya Angelou:

I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

Art catches and holds people’s attention by helping them feel new things. My work as a programmer, on the other hand, was forgettable. In fact, there’s a thing in software called the principle of least surprise: the better your code is, the less people even notice it exists. For a while, the thought of being unnoticed and forgettable left me with a sense of loss.

Relief came when I realized that although my code might never touch someone directly, it can (and has) helped artists who do. Just as the artist inspires the cancer researcher, the programmer empowers the artist. While the thought put an end to my mini existential crisis, some consequences remain, and that brings us back to asking for support.

Fans like Amanda Palmer’s give because they want to. They’re grateful for the gift of art, and they want to reciprocate. Emotion is a great motivator. But what about code? Software is complex, and beautiful, and important, but it doesn’t inspire the same emotion or generosity, because you never see the beauty. You can describe the types of things software will make possible, but that can seem overly abstract. I would like to think that crowdfunding can work for software as well as art. In fact, I’m currently running a campaign for software to manage makerspaces and other cooperatives. But how can programmers create the same connection with their users that artists create with their fans?

Advice for First Generation College Students

Some students entering college this fall have prepared their entire lives. But first-generation students, the first in their family to attend college, will leave their known world behind, with little idea of what to expect.

About a decade ago, I was one of these students. Neither of my parents went to college, and my father (despite being one of the smartest people I know) never finished high school. I stumbled my way through four years at MIT, figuring things out as I went, usually by making mistakes. Now I’m back at MIT as a staff researcher, and last year I had the opportunity to serve as an alumni mentor for MIT’s First Generation Project. I was delighted to find that I was able to help some bright young students by sharing my hard-learned lessons. I was also surprised at how common many of the experiences I had were. So I’d like to share those experiences and lessons here in the hopes that they’ll help current first-gen students, and help everyone understand us a little better.

Navigating the College Environment

College culture is very different from the environments–often minority, working-class, and/or immigrant–that first-gen students are used to. The most common adjustment for first-gen students is learning to ask for help! That can be difficult to do when you’re not used to there being anyone to go to. When I was growing up, I learned that asking for help made people do whatever they could to get me to go away. They had their own problems, they didn’t need to deal with mine too. In college, it was a huge revelation that people would not only help me, but be happy to do it (with occasional exceptions). Colleges want their students to succeed! Getting help means talking to peers and professors, studying in groups, going to office hours, asking questions in class, and seeking out resources for counseling or student life issues when needed. Another revelation was that I didn’t need a specific ask. I could go to someone with a problem, and they would help me figure out how to solve it–probably better than I could have on my own. Just as important as asking, is learning not to feel guilty for needing help, instead feeling and expressing gratitude.

Mentorship is one of the most powerful types of help you can seek. The realities of college life can be very different from official policies. Trying to navigate college life by-the-book is often an exercise in frustration, bureaucracy, and confusion unless you’ve learned to read between the lines. A good mentor can help. Mentors are also key for learning what you don’t know you don’t know. An ideal mentor is someone who looks like the kind of person you’d like to grow into. They’ve no doubt learned a lot along the way. They can help you avoid obstacles and direct you towards resources you never knew existed. Finding good mentors can be easier said than done, but the first step is learning to reach out to more experienced people who share your interests and passions.

First-gen students also face a sense of isolation. When you’re a part of two very different worlds, you never quite fit in anywhere. The good news is: that’s OK. It’s more important to become comfortable with yourself than it is to try to fit a mold. A mostly-empty dorm can feel particularly lonely when it seems like everyone has flown home for a long weekend, but you couldn’t afford to. But you’re often not as alone as it seems, and it’s important to find people you can relate to, who you feel comfortable around. For me, this was living in the beautifully dilapidated, graffiti-covered Bexley Hall. And with many colleges now offering first-gen programs, it’s increasingly easier to meet students with similar expereinces. On the flipside, it’s important to venture out of your comfort zone, to fully take advantage everything your new environment has to offer. One thing that helps is to remember that even when you feel like an outsider, it doesn’t necessarily mean others see you that way. You probably have a unique perspective to offer, and if they’re wise, they’ll appreciate that. Similarly, it can be tough to find yourself judged against people who have had more opportunities than you, but instead of resenting it, it’s wise to learn from the unique perspective that they have.

Money

If you’re the first in your family to go to college, chances are you’re paying your tuition with debt, and you won’t have much pocket change. There isn’t much you can do about that, but a few practical tips can make the financial squeeze a little more bearable. Student discounts are everywhere, especially in college towns, so always make sure to ask. Similarly, the Student Advantage card or a AAA membership can easily pay for themselves with discounts on travel and other purchases.

You’ll start getting credit card offers. The only cards you should consider are ones with no fee that offer cash back rewards (usually from 1-5%). If you do get one, never carry a balance. Never put more on it than you have in your checking account, and set a reminder for yourself to pay it off twice per month.

Textbooks are expensive. My textbook collection is still the most costly thing I own, and I’ve gotten rid of most of them! If you can, borrow your books from friends who have taken the class. Otherwise, rent or buy used books, and sell them as soon as you’re done with the class– the resale value drops quickly, especially if a new edition comes out.

Saving money is important, but one of the hardest things for a cash-strapped first-gen student to learn is that sometimes it’s better to spend it. A good rule of thumb is to spend extra money on things that will last a long time, and that will improve your life on a daily basis. That could be anything from a comfortable mattress, to bonding with a group of friends over dinner.

Family Obligations

The purpose of college is self-improvement, which requires a certain amount of self-centeredness. That can put first-gen students in a bind. Less privileged families are disproportionately affected by things like unemployment, physical and mental health issues, and incarceration. First-gen students can face an incredible amount of guilt for focusing on their studies while their families struggle. Trying to help your family and succeed in college can feel like you’re simultaneously playing two games with different rules, and you need to make the right moves to win both. The difficult truth is that, in most cases, focusing on your studies is better in the long run than letting them take the back seat while you help your family. As the cliché goes, you have to put on your own oxygen mask before you try to help anyone else.

I’ve personally struggled to find a balance obligations to myself and to my family, and over many years, I’ve settled on some guidelines that I’ve found helpful. For college students, earning potential is low and money is often more limited than time, so financial help is usually not the most efficient form. If you do need to help your family financially, make gifts, not loans. Counting on getting money back can set you up for catastrophes that are both financially and emotionally costly.

As an alternative to money, emotional support can be incredibly powerful, and the positive, thriving atmosphere of college can put you in a great position to offer it. Colleges usually offer great support and counseling for students, and by leveraging that to take better care of yourself, you can help provide a sense of stability and security to your family. You can also help your family in other non-monetary ways. For instance, if they need a new car, you could see whether anyone in your college network knows someone selling one for a good price.

Unfortunately, well-intentioned help can become unbalanced and unhealthy, so it’s important to develop strong boundaries. One rule of thumb is that if someone is capable of doing something themselves, doing it with them is ok, but doing it for them is not. Another good guideline is not to assume the consequences of anyone else’s decisions or actions. It can be incredibly hard to stick to these boundaries when people you love need help. Offering empathy and emotional support is often a good alternative. As a final thought, sometimes there just isn’t anything you can do to help. When that’s the case, remember that someday, you’ll be in a better position, and even though you can’t go back in time, you’ll be able to pay it forward and offer that help to your own friends, children, and mentees.

Abuse Is Not a Choice, Empathy Is

When we label someone an "abuser," we let them off too easily and invite future abuse into our communities.

Willow Brugh recently wrote a thoughtful post about how communities respond to abusive behavior. She writes, "If we simply kick out anyone who messes up, we end up with empty communities, and that’s not a new future." She calls for alternatives. The post sparked a lively twitter debate, with many arguing that abusers are aware of what they're doing and that placing the onus of "reforming" them on a community is overly burdensome. But, the rare sociopath aside, the very idea of an "abuser" is an anti-bogeyman that prevents us from dealing with the realities of abusive behavior in our communities, and importantly, in ourselves.

At this point, I should note that I'm no stranger to abuse. As a hackerspace director for many years, I was often in the position of responding when someone posed a threat to the safety and comfort of other members, and proudly, often the first person those members turned to for help. I've seen friends and family affected by abuse from strangers, relatives, police, lovers, and spouses. And, I've experienced abuse myself. I know the sting of betrayal, and the long-lingering doubt that comes from being mistreated by someone you trusted. I also know how difficult it is to recognize when your actions are hurting someone you care about, and how much work, dedication, and time it takes to change the thinking and habits behind those behaviors.

Discussions of abuse often insist it's a conscious choice. When asked about dealing with mean people, the terrific advice columnist Captain Awkward wrote:

I vote that you believe hard in the Mean Guy and view the rest of his personality through that lens. Because Sexy Guy is mean. And Sad Guy is mean. And I get it, because when you hate yourself and feel terrible, it makes it more likely that terrible things will escape your mouth. But at the end of the day, being depressed does not excuse being mean. Mean is a choice.

Yes, abuse is inexcusable, but the belief that it's a choice is both incorrect and harmful.

Consider the way a typical two-year-old treats others. They hit, lie, steal, threaten, scream, and any number of other behaviors that, if committed by an adult, would be undeniably abusive. But those children are not evil, they have not made a calculated decision to harm others. Their behavior stems from the inability to look past their own needs and consider the needs of others: in short, an underdeveloped sense of empathy. When I've worked to resolve conflicts in the hackerspace community, the abusive behavior I've seen has always stemmed from the exact same thing. If the offenders had been able to look past their own needs and emotions, they would have had to be either stupid or evil to act as they did (apologies to the Daily Show) but they couldn't.

Crucially, if someone believes abusive behavior is the result of a conscious choice, and they never made such a choice, they conclude that there is nothing wrong with their behavior. They then believe the problem must lie entirely with someone else. In other words, abuse is not a conscious choice, it is a lack of the conscious choice to empathize. Similarly, the false binary of "abuser" and "non-abuser" allows victims of abuse to assume that they could never become abusers themselves, when in fact, victims of abuse are the ones most likely become abusive (see Breaking the Cycle of Abuse: How to Move Beyond Your Past to Create an Abuse-Free Future). This is absolutely not an excuse for abusive behavior, but it suggests a completely different approach to understanding and responding to it. Have you ever looked critically at your own behavior towards others and considered that it might be abusive? If not, there's a good chance that, at times, it has been.

So how should we respond to abusive behavior within a community? I think Willow is right that we need something better than vilification and ostracization. When we say "we're kicking that person out because they're bad" we lose a crucial opportunity for the community to have a dialog about which behaviors are appropriate, and why. Also, no one sees themselves as "bad," so in such a system, they have no incentive to reflect on their own actions. In a wonderful video about how to tell someone they sound racist, Jay Smooth favors the "what you did" conversation over the "who you are" conversation, saying:

That conversation takes us away from the facts of what they did, into speculation about their motives and intention. And those are things you can only guess at, you can't ever prove, and that makes it way to easy for them to derail your whole argument.

What's more, when we label someone an "abuser" we fail to see them as people, modeling the very lack of empathy that causes abuse in the first place, furthering a vicious cycle. Should the recipient of abuse be forced to empathize with their abuser? No, of course not. But the response of the community, if it is to remain healthy, must be based in empathy. In practice, this means first and foremost, supporting and protecting the safety of anyone who was abused, and if at all possible, providing clear expectations to the perpetrator, along with an opportunity to meet them, and the consequences for not doing so. Some people will choose to continue harmful behaviors, and in doing so, choose to remove themselves from the community, but those who remain learn not to place blame, but rather to empathize and take responsibility for their own actions. People aren't problems. Problems are problems and people are people.

Return to Moderate Drinking is Still a Lie

Every few years, someone discovers that problem drinkers can return to moderate drinking—and they're always wrong. So when I saw an op-ed in the New York Times entitled "Cold Turkey Isn't the Only Route," I was disappointed, but not surprised. The op-ed, written by Gabrielle Glaser in support of her new book, has a simple message: for those who struggle to control their drinking, moderation is an alternative to abstinence. This claim is not new, and it's been disproven time and time again, often at the cost of human lives.

The first excitement over moderate drinking came after a 1962 case study by D.L. Davies. Of 93 patients treated for alcohol addiction, Davies found 7 who self-reported (with corroboration from family) drinking at most 3 pints (4 12 oz. drinks) of beer per day for at least 7 years after their treatment[1]. Although this sparked the first wave of claims that alcoholics could achieve moderate drinking, Davies' actual conclusion was that "the generally accepted view that no alcohol addict can ever again drink normally should be modified, although all patients should be advised to aim at total abstinence." Unfortunately, even that modest claim turned out to be based on bad data. A 1994 followup concluded that (surprise!) his patients had understated the severity of their drinking[2].

In the 1970s Mark and Linda Sobell picked up the torch. They devised an experimental technique to train alcoholics to drink moderately and tested it on 20 patients, concluding "some 'alcoholics' can acquire and maintain controlled drinking behavior over at least a 1-yr follow-up interval[3]." Based on those 20 patients, they wrote a book to teach their method to the general public[4]. In 1982, a team of scientists from UCLA did an independent review and follow-up with the Sobells' patients, finding very different outcomes:

Only one, who apparently had not experienced physical withdrawal symptoms, maintained a pattern of controlled drinking; eight continued to drink excessively—regularly or intermittently—despite repeated damaging consequences; six abandoned their efforts to engage in controlled drinking and became abstinent; four died from alcohol-related causes; and one, certified about a year after discharge from the research project as gravely disabled because of drinking, was missing[5].

In 1984, a Federal panel investigated the Sobell's for fraud. The panel found ambiguous language, errors, incorrect statements, and that the Sobells had "overstated their success," but attributed these discrepancies to carelessness rather than deliberate fraud[6].

The 1970s also saw an oft-cited study from the RAND Corporation, reporting that moderate drinking didn't predict relapse in patients previously treated for alcohol problems[7]. But that study only followed patients for six months. A four-year follow-up by the same researchers found that many of the original study's "moderate drinkers" had relapsed[8][9].

In Wednesday's op-ed, Glaser mentions a program called Moderation Management (MM) and reports meeting many women who have used it to change their drinking habits, but she doesn't go into MM's history. In 1994, on the heels of the Sobells' study and the first RAND report, a woman named Audrey Kishline came across the research on moderate drinking. She believed she was a problem-drinker, but not a chronic drinker, and embraced moderate drinking as her goal. Then, under the guidance of the Sobells, and contemporary moderate-drinking proponents Jeffrey Schaler, Stanton Peele, and Herbert Fingarette, she founded Moderation Management. She wrote a book, analogous to AA's "big book," to help other problem-drinkers like herself find an alternative to abstinence[10]. MM continued to grow and gain members over the next 6 years.

Then, on March 25, 2000, Kishline crashed her truck into oncoming traffic on Interstate-90, killing a 38-year-old man and his 12-year-old daughter. At the time, Kishline had been on a two-day vodka bender. She later admitted to NBC that while running Moderation Management, she'd been breaking her own rules, drinking at least 3 or 4 drinks a day, every single day, and sometimes binging on 7 or 8[10]. In her interview, she said she still believes problem-drinkers can achieve moderation as long as they're not truly alcoholic, but when asked where that line is, she replied "Nobody knows."

Kishline's experiment failed, and the small-scale, short-term, self-reporting studies claiming to show a return to moderate drinking have all fallen apart under scrutiny. The longest, largest study of the behavior of problem-drinkers has been by Harvard's George Vaillant, who studied over 600 subjects from the 1930s to present day. His conclusion: "Training alcohol-dependent individuals to achieve stable return to controlled drinking is a mirage.[9]"

In Glaser's defense, she does qualify her claims, saying "This approach isn’t for severely dependent drinkers, for whom abstinence might be best." But (almost) no one suggests abstinence unless a drinker is already having problems. If you want to drink less, try drinking less. If that works, you don't need a book, if it doesn't, there's probably no book that can help you. Glaser's book follows the path laid out by the Sobells, Kishline, Schaler, Fingarette, and Peele: helping no one, and exploiting the hopes and denial of the chronically mentally ill.

If you'd like a credible source of information on alcoholism, I highly recommend Alcoholism: The Facts by Ann M. Manzardo et al. and The Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited by George E. Vaillant. For a more personal account, Drinking: A Love Story by the late Caroline Knapp is honest and brilliant. Let's finally put the myth of return to moderate drinking to rest.

[1] D.L. Davies. "Normal Drinking in Recovered Alcohol Addicts." Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol 23 (1962): 94-104.

[2] G. Edwards. "D.L. Davies and 'Normal drinking in recovered alcohol addicts': the genesis of a paper" Drug and Alcohol Dependence 35.3 (1994): 249-259.

[3] M. Sobell, and L. Sobell. "Alcoholics Treated by Individualized Behavior Therapy: One Year Treatment Outcome." Behavior Research and Therapy 11 (1973):599-618.

[4] M. Sobel, and L. Sobell. Behavioral Treatment of Alcohol Problems: individualized therapy and controlled drinking. Springer, 1978.

[5] M.L. Pendery, I.M. Maltzman, and L.J. West. "Controlled Drinking by Alcoholics? New Findings and a Reevaluation of a Major Affirmative Study" Science 217(1982):169-175.

[6] P.M. Boffey. "Panel Finds No Fraud by Alcohol Researchers." New York Times. September 11, 1984.

[7] D.J. Armor, H.B. Braiker, and J.M. Polich. Alcoholism and treatment. Rand, 1976.

[8] J.M. Polich, D.J. Armor, and H.B. Braiker. The Course of Alcoholism: Four Years After Treatment. Rand, 1980.

[9] G.E. Vaillant. The Natural History of Alcoholism Revisited. Harvard University Press, 1995.

[10] A. Kishline. Moderate Drinking: The Moderation Management Guide for People Who Want to Reduce Their Drinking. Crown Publishing Group, 1994.

[11] D. Murphy. "Road to Recovery." Dateline. NBC. Sept. 1, 2006.

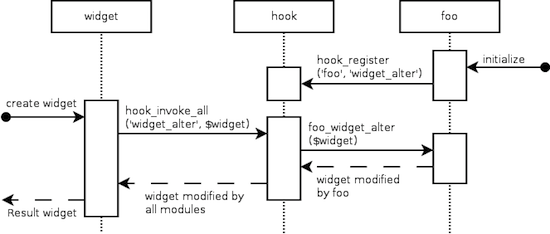

Drupal Hooks Should Use PubSub

Drupal is an incredibly flexible piece of software, but that flexibility often comes at the price of slow performance. After several years working on Seltzer CRM, which I modeled after Drupal 6, I've realized that there is a simple way to get the same flexibility without as much of a hit to performance.

Drupal achieves its flexibility through modules and hooks. A Drupal module is simply a self-contained chunk of code that can be installed and enabled to provide a set of features, like a shopping cart, or comment moderation. A hook is a function in one module that changes the behavior of another module, like taking a form produced by one module, and altering its contents. Drupal's takes an implicit approach. If I have a module foo and I want it to alter forms produced by other modules, I implement the hook_form_alter() hook like so:

function foo_form_alter(&, &, ) { ... }

Whenever the form system creates a new form, it checks each module to see if hook_form_alter() is implemented, and if it is, passes the form data through that function. All my module needs to do is define the function. So what's the problem?

The performance problem is in plain sight. Every time a hook is called, every module needs to be checked for the existence of that function. The number of checks increases linearly with the number of modules, and in practice, most of those checks are unnecessary because any given hook will only be implemented by a small fraction of available modules. We can improve performance by switching to an explicit approach.

For our first try, let's invent a function called form_alter_register() that allows our module to explicitly register a callback:

form_alter_register('foo_form_alter');

function foo_form_alter(&, &, ) { ... }

Now, the form system can check each callback in the list rather than checking each module, which could speed things up quite a bit!

However, we're not quite at the same level of flexibility yet. Let's imagine that there's another module called "widget" and if its installed we want to be able to alter widgets as well. We do the following, right?

widget_alter_register('foo_form_alter');

function foo_widget_alter(&) { ... }

It works fine if the widget module is enabled, but what if the widget module is optional? Then widget_alter_register('foo_form_alter') won't be defined, and our code will crash! We could check whether the function exists before calling it, but that could get tedious. Better yet, we can use the same trick again, resulting in something like a publication-subscription approach.

Specifically, we define two core functions, one that allows modules to register the hooks they implement, and one that calls all hooks of a given name:

function hook_register(, ) { ... }

function hook_invoke_all() { ... }

Then our code to implement the hook looks like this:

hook_register('foo', 'widget_alter');

function foo_widget_alter(&) { ... }

Now we have improved performance and the same level of flexibility. Some might argue that even calling hook_register() before each hook definition is tedious, and it may be. On the other hand, code is read more than it is written (as the adage goes) and this pattern explicitly identifies a hook as such, making it more readable, while Drupal's current pattern does not. So for improved performance and readability, the next time I'm writing a modular framework, I'm likely to use this pattern instead.

PS: Does anyone know if there is a proper design pattern name for either of these approaches?

Sustainable Hackerspaces FTW

Last Friday, the CEO of i3 Detroit announced his resignation, and Bucketworks in Milwaukee announced that they were raising money to help make rent (they did). Both announcements generated a lot of valuable discussion about the sustainability of hackerspaces, but there are a few important points that I believe are often overlooked when talking about sustainability.

Growth hurts sustainability. Expanding membership numbers or square footage sounds like a good thing for a hackerspace, but it also carries downsides, especially when that growth happens quickly. More members and more space means more to manage, which means a higher burden on the leaders of a space. A quick influx of new members can weaken the community because those new members take time to learn the group’s social norms (e.g. how to “be excellent,” as so many spaces encourage). It also takes time for new members to learn how to contribute back to the space, so even if they want to, they won’t at first.

At i3 Detroit, they’ve implemented a mentor system where all new members are assigned a mentor (similar to the time-tested big brother/sister system used in fraternities and sororities). Mentors are a single point of contact to help new members get acquainted with the space, its rules, and its values. It’s a new program, but it seems like a great way to tackle the instability that comes with growth, and I have high hopes for it. Have any other spaces tried this technique, or others, to combat the instability associated with rapid growth?

Fundraising is good, saving is better. Many spaces run very close to the break-even point, so when the natural oscillation of membership goes down, or they have to make an unexpected repair, they need to have a “rent party” to quickly come up with money to make ends meet. The alternative is to regularly contribute to an emergency fund. One benefit of such a fund is that even if you still need to have a fundraiser, it buys you time. That extra time opens up new possibilities, like getting more quotes on a repair, or even finding a new space. Plus, extra time makes it a lot easier to continue keeping the space running smoothly for members while dealing with financial issues, without burning out.

But spaces can save for more than just emergencies! Even nonprofit spaces can have investment savings and use interest and dividends to offset operating costs. It takes a long time to build these kinds of savings up, but once you have them, it’s that much easier to weather hard financial times, fund special programs, offer reduced dues for those in need, and so on. Many universities, for instance, use these kinds of funds, called endowments. Similarly, hackerspaces should be considering saving to buy their own buildings. I’m not aware of any that have done this, but owning rather than renting would lower monthly expenses for most spaces (even if they have to get a mortgage) and would prevent the common problem of landlords raising rent after a group has invested in repairs and improvements to their space.

Finally, hackerspaces are businesses. This is a controversial statement, but I believe that if the leaders of a hackerspace aren’t treating it like a business (keeping accurate books, financial planning, catching problems before they snowball, etc.) then they are doing a disservice to the members and setting themselves up to burn out. That said a hackerspace should not feel like a business to the members. Hackerspaces work best when members can come in and just hack, teach, and learn with a minimum of obstacles. In good hackerspaces, the administrators consistently remove those obstacles, and in great hackerspaces they do it before the members even notice them.

There is a lot of good common wisdom floating around on design patterns for hackerspaces and common traps to avoid. Now that so many hackerspaces are up and running, I’m hoping to see more attention turn to how to ways to keep them running, not just for 5 or 10 years, but for future generations.